(Editor’s Note: Continued from from Old 666: Fantastic Voyage of the Cursed Bomber – Part One)

The Japanese started reducing their attack runs, preferring short bursts due to the B-17’s incredible defense. They had never faced so much resistance from one plane. With three comrades gone in flames and several more nursing damaged aircraft, most of them ended up staying behind just out of machine gun range, watching to see if the bomber would plunge toward the sea.

Instead, Zeamer, shrugging off first aid, and going in and out of consciousness, somehow got the bomber back on course for home and continued to keep it steady.

Behind him, the Japanese continued chasing almost as if in formation, licking their chops waiting for the final attack order, until the strangest thing happened. One by one they began to peel off, fuel gauge needles starting to hover over the vital safe return mark, but each felt confident Old 666 would begin its death dive long before it made it back to dry land.

With its hydraulics and oxygen gone, Zeamer knew they might not make it as well. The B-17 was barely flyable and losing altitude. When nearing the New Guinea coast, he realized they would never make it over the formidable Owen Stanley mountain range before reaching Port Moresby. He asked Britton to take over and land at the closer fighter airstrip at Dobodura before he lost consciousness a final time. Britton shook Zeamer trying to wake him.

He appeared dead.

Britton took the controls and veered the plane toward Dobodura, notifying them of the emergency situation. When he was given clearance to land he knew they still might not make it. Old 666 stuttered and creaked as if it were about to fall apart. With the runway coming into view, Britton aimed for it as best he could, narrowly keeping above the trees and landing the plane, not knowing if the landing gear or brakes worked.

The moment the plane hit, he realized the gear was down but the brakes were gone. Therefore, his only option was to groundloop it. He turned the control wheel until a wingtip dug into the dirt, causing the plane to spin around and suddenly stop, disappearing in a cloud of dust. He killed the engines just as dozens of personnel and vehicles converged from all directions.

Old 666 wept and steamed with sizzling fuel and oil as the hatches were pulled open. Peering inside, rescuers eyes gaped, shocked at what they saw. Five of the nine men were wounded, blood splattered all around their positions. Those looking into the shattered nose saw Sarnoski slumped face down, lifeless as streams of blood formed in spidery like lines from his body.

Then they reached Zeamer.

His uniform was stained dark and blood dripped from his seat to pool around his boots. His head hung over, limp, eyes closed, his face punctured in several places and bleeding. Britton urged the medics to try and revive him. He heard one of them say “Forget it, he’s dead.” They unstrapped him and loaded him up and drove away as Britton and the rest of those who could walk were helped away from their wrecked bird.

Others who witnessed the crew being removed on stretchers could hardly believe the carnage they must have endured. The base commander asked for and received names of the dead to notify Port Moresby. Jay Zeamer was among them. Glum faces wrote and mailed two death notices off to families. By now, after witnessing their past acts of courage, Zeamer’s commander held enormous respect for Old 666’s crew, more so, as he continued to hear of their heroism over Bougainville.

He knew there would be no more whispering about the crew behind their backs, about how they were screwups given the worst plane to make do. Nobody could top what they had just done. After June 16, they were the epitome of heroism, especially the two dead. What he could not know, however, was that there was a bright spot in the ordeal. With his death notice on its way across the Pacific, one Jay Zeamer lay on an operating table very much alive, though barely.

He came-to while being carried away and the surprised personnel whisked him to the hospital. There, he underwent hours of surgery to remove 120 pieces of shrapnel from his body, which had caused the loss of more than 50% of his blood. A call went out for donors, and a long line of volunteers eagerly offered their portion. It was touch and go for the next seventy two hours, the most critical time, but Jay Zeamer stabilized in critical condition.

Port Moresby received notification, but it was too late to stop the telegram heading for the states. After reaching his parents weeks later, they breathed a sigh of relief when they were told it was a mistake. Sadly, Sarnoski’s wasn’t and long before Zeamer’s parents relief, Old 666 crew members who were able to attend watched the burial of Lieutenant Sarnoski on a small hill in New Guinea. Zeamer was not among them, having just begun an agonizing, slow recovery that would take him through fifteen months of rehabilitation. Lying immobile in his bed, he hoped the photographs they risked everything for were worth something.

The camera carrying the vital film was flown to Port Moresby, then driven to a darkroom and poured over for their information. What emerged proved invaluable in mapping the coast. Topography teams revised Bougainville’s contours and figured new ways to get through a coral reef, further defined this time. These updates enabled untold numbers of lives to be saved when forces moved ashore November 1st to begin wresting the island from the Japanese.

To all, Old 666’s crew did a job beyond well done.

Their exploits reached the highest levels of command, namely General George Kenney, commander of the 5th Air Force, to which Zeamer’s group belonged, and General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces. Without hesitation, these men decided the heroism and effectiveness Old 666’s crew needed to be rewarded.

Sarnoski and Zeamer received recommendations for the Medal of Honor which were quickly approved, while the rest of the crew received the second highest award, the Distinguished Service Cross. On January 16th, a still recuperating Zeamer, now a Major, watched General Arnold place the medal around his neck. Humbled, he still thought of his crew, in particular Sarnoski. In April, he was promoted again to Lieutenant Colonel, and he knew the days with his crew and Old 666 were now but a memory as they were scattered across the globe still flying missions, something he could no longer do. Never able to fully recover from his wounds, he medically retired from the service in January 1945, commander of the most decorated air mission in U.S. history

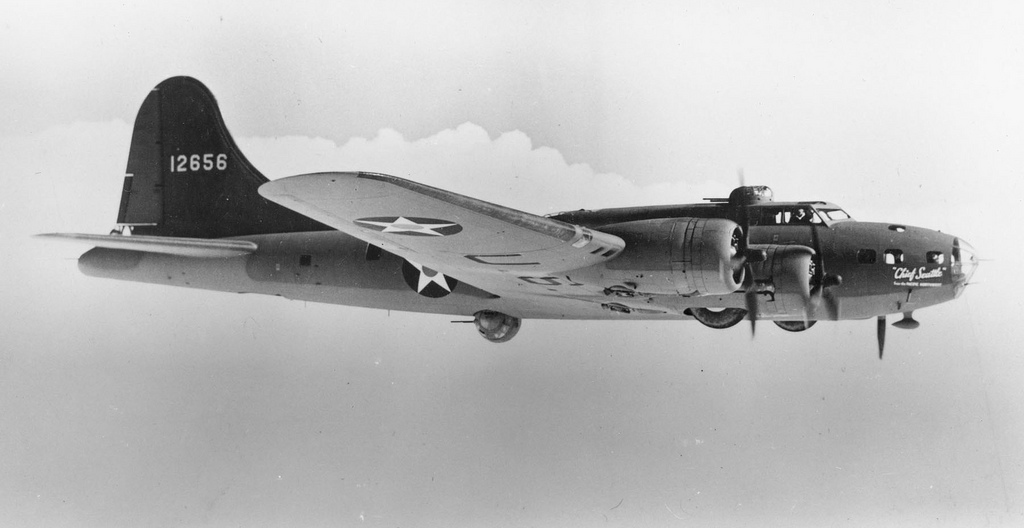

So what became of Old 666? Towed off the flightline, it was patched up again and eventually made airworthy. It continued flying missions with different crews until replaced by the more powerful F and G series B-17s and B-24 Liberators. Old 666 returned to the U.S. in February, 1944 at Albuquerque, New Mexico and stayed in reserve until it was turned over to a scrapyard in August 1945. Numerous patches covered its many wounds, but like before, it’s a safe bet it was no less willing to go in harm’s way one more time.